The sustained decline in Brazilian inequality levels has been of the most striking aspects of its development performance over the last 10 years.

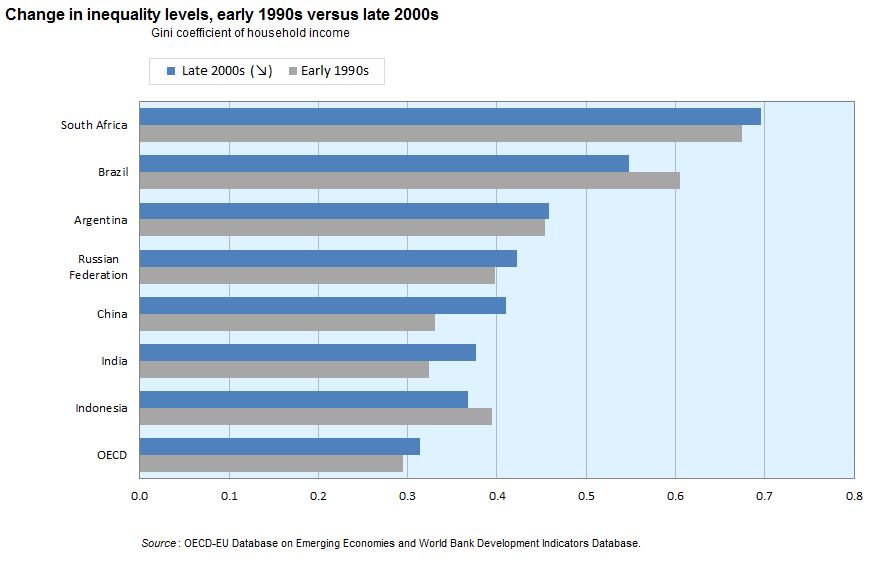

In addition to raising an estimated 40 million people out of poverty, the Brazil’s GINI coefficient fell by 12%, from 0.59 in 1995 to 0.52 in 2012. While inequality in Brazil remains high, this reduction stands in stark contrast to other BRICS and OECD countries, which have seen levels rise.

So how has Brazil been able to reduced inequality levels?

It is estimated that 35-50% of the reduction in inequality in Brazil can be attributed to changes in non-labour incomes, largely as a result of growing social assistance programmes.

Despite costing just 0.7% of GDP, the extremely effective targeting of the Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer scheme has been vital. Brazil’s other social pension schemes have also made important contributions to the decline.

A further 10% or so can be attributed to demographic factors, particularly the declining household size among poorer families.

The remaining 40-55% is attributed to changes in the distribution of labour earnings. So far, the dominant explanation for this has been the effects of a better educated workforce, but new research for the IRIBA project led by the World Bank’s chief economist for Africa, Francisco Ferreira, challenges this finding.

While most of the previous research pointed to the effects of an increasingly educated workforce, the new findings highlight the importance of demographic, spatial and institutional factors in explaining the decrease in earnings inequality.

We found that the main factors behind the decline in earnings inequality were lower gender and race wage gaps, and lower urban and regional wage premia. There was also a reduction in the gap between formal and informal sector workers. In the latter part of the period of study (2004-2012), a rising minimum wage also contributed.

Professor Sergio Firpo talks more about the findings in this video:

Could other developing countries follow suit?

While it would not be possible (or desirable) for any country to attempt to copy Brazil’s approach in its entirety, there are a number of broader policy implications that come out of the IRIBA research. We believe that learning from the Brazilian development experience could be particularly useful for many growing economies within Africa.

- An educated labour force is a more productive labour force and, if education is promoted wisely, with a focus on primary and secondary levels, it leads to greater prosperity and greater equity;

- All forms of discrimination – among the sexes, ethnic groups, or other forms – tend to be both inefficient and inequitable. Encouraging female education, reduction in fertility rates, and greater labour force participation has contributed to growth in average earnings, and to a less unequal distribution in Brazil.

- Integrate the rural areas, and the workers who live there: greater connectivity and less labour market segmentation between cities and the countryside are an ongoing part of Brazil’s recently successful fight against poverty and inequality.

- And finally, do not fear fiscal redistribution: well-designed transfer programmes are perfectly consistent with vibrant labour markets, with rising average wages and declining dispersion.

This post is a contribution to Blog Action Day 2014.