For the Brazilian minister for Social Development, Tereza Campello, ‘teaching a man to fish’ is only part of the story. You also need to show him the way to the river and if he’s too hungry to fish in the first place – just give him some of your fish!

Campello’s impassioned take on the responsibility of the state to play an active role in the fight against poverty and inequality came at the end of a fascinating conference organised by Favelas@LSE. The findings of its Underground Sociabilities project knitted the day together, to give a unique insight into the experience of Brazil at both a national and street level – through the eyes of Minister Campello and some of Rio’s favela dwellers.

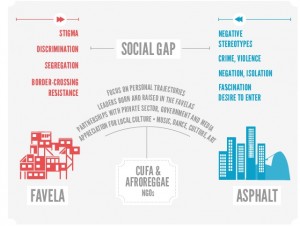

Professor Sandra Jovchelovich set the tone for the day, with an outline of the Underground Sociabilities findings. The project looked at the lives of people living is Rio’s favelas and their use of cultural organisations to challenge negative stereotypes and influences. The (free) e-book is well worth a read.

Campello, followed by IRIBA’s Armando Barrientos outlined the nature of progress at the national level in Brazil. Campello was one of the original architects of Bolsa Família and is clearly proud of the impact it has made, particularly on levels of extreme poverty experienced by children. In 10 years, the number of children living in extreme poverty has fallen by 89% and now stands at under 1% of the population.

Despite the progress, Campello is clear that the job is not yet finished. Millions may have escaped from extreme poverty, but they’re still very poor. A key aspect of the government’s drive to make further progress is the creation of a full-blown welfare state. This has been the intention from the start, but often gets missed in the focus on individual programmes (like Bolsa Família).

Corroborating the IRIBA findings on the importance of the social contract to addressing poverty in Brazil, Campello repeatedly stressed the responsibility of the state to root out poverty. This is encapsulated by recent efforts to actively seek out the few hundred thousand hard to reach Brazilians still living in extreme poverty.

Arguing that inclusive growth was the distinctive feature in Brazil’s development performance, Professor Barrientos outlined the main IRIBA findings and his own research on the impact of Brazilian antipoverty transfers:

Reflecting on the implications for the UK (and potentially other countries), he highlighted:

- That the contribution of effective social policies is essential to secure inclusive growth

- That social investment is complementary to growth and human development

- The importance of sustaining social contracts based on a concern for the least advantaged

In contrast to the dreaded post-lunch slump featured in many day-long conferences, the infectious energy, enthusiasm and ideas of favela activists like CUFA’s Nega Gizza and citizen journalist Rene Silva dos Santos was startling. Their very real struggles with poverty, violence and a lack of opportunity in Rio’s favelas was set against their incredible sense of dynamism and agency.

While the minister discussed the social contact in more overt terms, I realised that the attitude and contribution of people like Nega and Rene is a vital aspect of Brazil’s much larger project. Although they’d both experienced difficult times and setbacks, both had an inspiringly positive outlook for themselves and their communities.

The sense of both a bottom-up and top-down vision and action towards improving life for all Brazilians was palpable – and certainly helped me to see the IRIBA findings in a much more vivid context.