Today Brazil is one of the major producers of a series of agricultural commodities, including soybeans, sugar, orange juice, maize, cotton, chicken, meat and pigs, with strong participation in a long list of others. The position of Brazilian agriculture as one of the breadbaskets of the world is quite remarkable given that just two decades ago this sector was marked instead by backwardness and inefficiencies.

This has been achieved not by simply incorporating more land, but by dramatic improvements in productivity, led by technological research that developed methods and inputs specifically suited to the country’s conditions. The government’s agricultural research institute, EMBRAPA, has been responsible for coordinating and catalysing many of these developments.

At a recent seminar held at the University of Brasília, we discussed the different factors underlying the transformation in Brazilian agriculture and, given the similarities, what African countries could learn. Each presentation and a short interview with the lead researchers is below.

The Economics of the Brazilian Model of Agriculture from The International Research Initiative on Brazil and Africa (IRIBA)

What explains the intensification of Brazilian agricultural production? from The International Research Initiative on Brazil and Africa (IRIBA)

Technological catch up: EMBRAPA's role in supporting Brazilian agriculture from The International Research Initiative on Brazil and Africa (IRIBA)

Read our research on Brazilian agriculture.

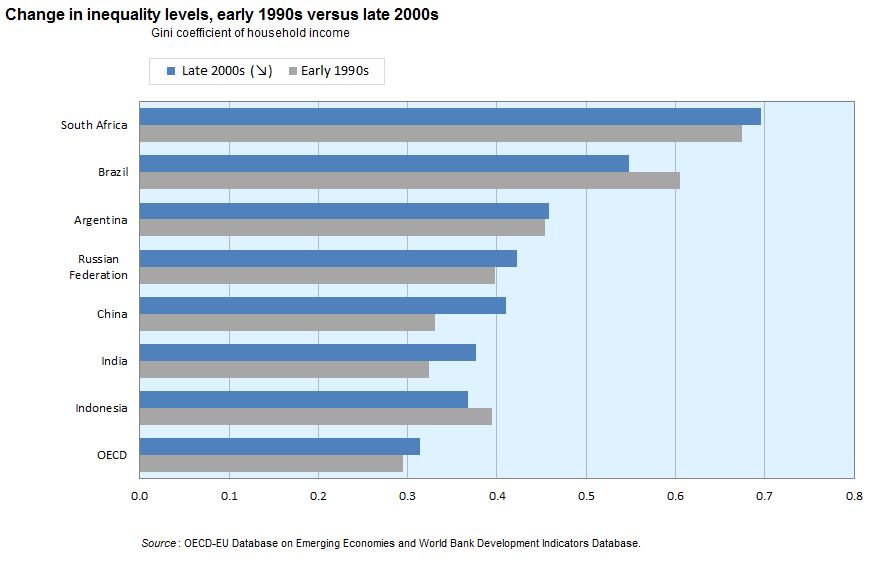

The sustained decline in Brazilian inequality levels has been of the most striking aspects of its development performance over the last 10 years.

In addition to raising an estimated 40 million people out of poverty, the Brazil’s GINI coefficient fell by 12%, from 0.59 in 1995 to 0.52 in 2012. While inequality in Brazil remains high, this reduction stands in stark contrast to other BRICS and OECD countries, which have seen levels rise.

So how has Brazil been able to reduced inequality levels?

It is estimated that 35-50% of the reduction in inequality in Brazil can be attributed to changes in non-labour incomes, largely as a result of growing social assistance programmes.

Despite costing just 0.7% of GDP, the extremely effective targeting of the Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer scheme has been vital. Brazil’s other social pension schemes have also made important contributions to the decline.

A further 10% or so can be attributed to demographic factors, particularly the declining household size among poorer families.

The remaining 40-55% is attributed to changes in the distribution of labour earnings. So far, the dominant explanation for this has been the effects of a better educated workforce, but new research for the IRIBA project led by the World Bank’s chief economist for Africa, Francisco Ferreira, challenges this finding.

While most of the previous research pointed to the effects of an increasingly educated workforce, the new findings highlight the importance of demographic, spatial and institutional factors in explaining the decrease in earnings inequality.

We found that the main factors behind the decline in earnings inequality were lower gender and race wage gaps, and lower urban and regional wage premia. There was also a reduction in the gap between formal and informal sector workers. In the latter part of the period of study (2004-2012), a rising minimum wage also contributed.

Professor Sergio Firpo talks more about the findings in this video:

Could other developing countries follow suit?

While it would not be possible (or desirable) for any country to attempt to copy Brazil’s approach in its entirety, there are a number of broader policy implications that come out of the IRIBA research. We believe that learning from the Brazilian development experience could be particularly useful for many growing economies within Africa.

- An educated labour force is a more productive labour force and, if education is promoted wisely, with a focus on primary and secondary levels, it leads to greater prosperity and greater equity;

- All forms of discrimination – among the sexes, ethnic groups, or other forms – tend to be both inefficient and inequitable. Encouraging female education, reduction in fertility rates, and greater labour force participation has contributed to growth in average earnings, and to a less unequal distribution in Brazil.

- Integrate the rural areas, and the workers who live there: greater connectivity and less labour market segmentation between cities and the countryside are an ongoing part of Brazil’s recently successful fight against poverty and inequality.

- And finally, do not fear fiscal redistribution: well-designed transfer programmes are perfectly consistent with vibrant labour markets, with rising average wages and declining dispersion.

This post is a contribution to Blog Action Day 2014.

“Brasil” by Roger Schultz (CC BY 2.0)

By Marcus Melo, professor of Political Science at the Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil, and Armando Barrientos, co-research director of IRIBA. Cross-posted from the Tax Justice Network blog.

Internationally, debates on tax in Brazil often focus on its refusal to adopt OECD transfer pricing guidelines, but the country’s domestic arrangements also offer a fascinating window on its impressive development progress.

Over the last 10 years Brazil has lifted an estimated 40 million people out of poverty, while reducing inequality by around 12%. Since the mid-1990s, the country has undergone a transformation – and tax, redistribution and the social contract have played a pivotal role.

Brazil managed a remarkable 7% increase in tax revenue as a percentage of GDP between 1995 and 2010, a rise from 26.9% in 1995 to 34% in 2010. We wanted to understand how this had come about and what other developing countries could learn from it.

The big rise in Brazil’s revenue base is not the result of any significant change in tax codes or administration. Economic growth has played its part, but unlike many African countries, which are struggling to convert the proceeds of growth into increased revenues, Brazil has capitalised on comprehensive tax reforms undertaken in the 1960s. Brazil adopted a modern tax code, became the first country to introduce VAT and revamped its tax administration.

The legacy of these reforms was a broader tax base, which has helped to stabilise the economy and critically, to establish the technical skills and capabilities needed to manage a large tax system. The downside has been the evolution of an extremely complex, and in many ways inefficient approach to tax collection, not helped by the federal structure of the country.

The incidence of taxation across society is relatively neutral, with the progressivity of direct taxes neutralised by the regressivity of indirect taxes. Despite growing calls for a simpler, more progressive system, successive governments have converged on the view that redistributive objectives are best secured via spending, not taxation.

Economic growth and the rise of the tax/GDP ratio in Brazil have enabled successive governments to expand inclusive social policies without the need to reallocate resources from existing programmes and therefore avoid damaging conflict. The flourishing of social assistance programmes in Brazil has been made possible by increasing tax revenues. The internationally feted Bolsa Família anti-poverty transfer programme was able to expand from covering 6.5 million households in 2004 to 14 million in 2013. Other less-known programmes such as Brazil’s two social pensions reach over 10 million people (with a budget twice that of Bolsa Família’s). Both poverty and inequality levels have fallen sharply as a result.

The political commitment to expanding redistribution throughout society has its roots in Brazil’s transition from dictatorship to democracy. The early years of civilian rule saw a strong consensus form around the need to tackle the ‘social debt’ created under military rule. The incorporation of previously disenfranchised ‘illiterates’ into political life created a large constituency for redistribution.

Indeed, the higher rates of tax paid by large companies and the assertive approach to transfer pricing are a reflection of the priority Brazil places on raising and redistributing revenues to its poorest citizens, over the desires of business.

As Brazil’s economy has slowed over the last few years, the ability of the government to continue to expand investment in social policies has been severely curtailed. Members of the emerging middle classes have been described as increasingly having a ‘dissatisfied customer’ relationship with the state; they are not content with the quality of public services they receive for the tax contribution they make.

With a forthcoming presidential vote, Brazil is now facing a critical juncture. The high level of taxation, the increasing politicisation of the issue and the pressures for better quality in public services are straining the previous consensus. This may result in less corruption and better services in exchange for tolerating high taxes, but the final outcome is far from certain.

Read the full research paper: Taxation, redistribution and the social contract in Brazil.

TJN adds: see also Tatiana Falcao’s 2012 article on Brazilian transfer pricing rules and her earlier, longer article for TJN.

On November 14, IRIBA co-research director Armando Barrientos will be participating in a UK-Brazil dialogue at the LSE, alongside Brazilian Minister for Social Development, Tereza Campello.

The event is being organised by the always interesting Favelas@LSE and tickets are available via favelas@lse.ac.uk.

This morning in the Guardian, IRIBA co-research director Ed Amann gives his take on the anti-poverty agenda facing Brazil’s presidential candidates.

This is a year of important anniversaries for Brazil. It is 10 years since the launch of the celebrated Bolsa Família anti-poverty plan and 20 years since the launch of the Brazilian real currency, a critical step on the path to economic stability. This month’s elections mark the 20th anniversary of the election of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso, a key architect of the real and instigator of predecessor programmes to the bolsa.

As the electorate goes to the polls, voters may feel cause for satisfaction. Over the past two decades the incidence of poverty has fallen, income distribution has become less skewed and Brazil has managed to combine reasonable growth with single-digit inflation. Yet many fear these achievements may not be sustained. This has undermined support for the presidential incumbent, Dilma Rousseff, who now faces a closely fought runoff against the centre-right candidate, Aécio Neves.

After comparatively strong growth in the early part of this decade, the Brazilian economy has entered a slump. The Central Bank now predicts GDP growth of only 0.7% this year. What’s more, the rapid pace of social and economic reform of the 1990s and 2000s has slowed under the Rousseff administration.

The elections therefore come at a crucial moment in the country’s battle to achieve more inclusive growth and to drive down poverty. Can the momentum be regained?

This question has no easy answers but a key starting point, as our research makes clear, is to recognise that the factors which have driven poverty down stretch well beyond Bolsa Família. They comprise an effective social contract (which provides political underpinning for difficult reforms); robust institutions and frameworks for counter-inflationary macroeconomic management (developed in the early years of the real); and effective, targeted social policies (including, but not limited to, the bolsa).

Supporting these elements was a favourable external economic environment in which foreign capital was abundant (and cheap) and commodity exports were healthy (and expensive). Across most of these dimensions, the horizon is undoubtedly darker today than it was even three years ago. It should not be beyond the ability of the next president to navigate these choppier waters, but the issues below must be addressed.

Consensus for reform

The achievement of consensus inside and outside Congress to push through difficult reforms was a hallmark of the successful real stabilisation plan in the 1990s. Yet, it is proving harder to build such a consensus today, certainly among the political elite. The case of long-delayed (and much-needed) fiscal reform is a telling example.

While it may be argued that Neves has a greater appetite than Rousseff for critical structural reforms (in areas such as tax and social security), he would still have to contend with powerful inertial forces. During the 1990s, a sense of crisis proved sufficient to galvanise politicians and society at large behind economic stabilisation. The current absence of crisis makes such a trick harder, but not impossible, to pull off today.

Effective macroeconomic management

The counter-inflationary framework developed during the 1990s and early 2000s remains in place. It is unlikely to be seriously amended, no matter who wins the election. Although effective at restraining prices to single digits (inflation is forecast to end the year at 6.3%), the high interest rates check economic growth. This has consequences for the speed at which poverty can be tackled and represents a real challenge in the short to medium term.

Targeted social policies

The most high-profile aspect of Brazil’s successful attempt to drive down poverty has been targeted social policies, among them the Bolsa Família. Their popularity ensures they face little chance of being rolled back, regardless of whether Rousseff or Neves is elected. In fact, many on the left and centre grounds of Brazilian politics would like to see their scope extended, with more emphasis given to improving access to quality education and public health services.

The objective is to endow poorer groups with the skills they need to break intergenerational cycles of deprivation. Whether such ambitions can be soon realised is open to doubt. In the absence of meaningful fiscal reform and with faltering growth, the financial scope for expansion is very limited.

The external environment

Future prospects for inclusive growth partly lie outside Brazil’s control. The state of the global economy will have a critical influence on the speed at which the domestic economy grows. The unwinding of quantitative easing and softening commodity prices will make it harder for Brazil to export and draw in investment. This will dampen growth prospects and further limit the fiscal space for spending on social programmes.

It is clear that the next administration will face serious challenges if it is to build on the accomplishments of recent years. However, Brazil is assuredly not in crisis. The popular clamour for progressive reform and social justice is also louder than ever. Opportunities for positive change exist, but it will take determination and persistence to seize them.

Opening yesterday’s International Economic Forum on Africa, OECD head Angel Gurría reiterated his organisation’s strapline: “better policies for better lives“. As the conference unfolded however, it became increasingly apparent that Africa isn’t lacking in good policies, but in the effective implementation of those policies.

Focussing on “industrialisation for inclusive growth“, the forum covered much of the same ground as our research examining the Brazilian development experience. Debates ranged from the importance of infrastructure, technology and human capital, to macroeconomic management and international trade. Underlying much of the debate was the question: why are the 5% growth rates across the continent not translating into sharper declines in poverty?

While there was broad consensus about the importance of promoting industrialisation, the track record in many African countries of stagnating, or even declining industrial output was stark. Indeed, it was estimated that despite the impressive growth rates, industrial output has actually reduced by 2% across Africa over the last 10 years.

Kako Nubukpo, the national planning minister for Togo identified the contradictory policy agenda driving this apparent paradox, with “customs duties disarmament” undermining the ability of many domestic industries to develop and compete with cheaper imports.

Head of the ECA Carlos Lopes suggested that without using “smart protectionism“, there was little hope for catalysing industrial development in most African countries. Unfortunately, there was little follow-up debate on this critical point, and the opportunity to look at the (in)coherence in policymaking and the political trade-offs involved was lost.

The contrast to the relatively clear social and economic vision pursued by Brazil appeared stark. Admittedly, the social contract and consensus underpinning the policy orientation of the country was formed in reaction to the long denial of democracy under the military dictatorship. But surely there are other ways for countries to forge a more coherent and inclusive approach to development?

Many of the panellists highlighted the current deficit in African political leadership to turn sound policies into tangible change on the ground. The self-described “most famous unemployed African”, Mo Ibrahim was particularly critical of African leaders signing regional agreements on economic integration, but then failing to make any real moves to implement them. He also took leaders to task for retaining office into their 90s, when most people across the continent were in their 20s.

Despite AU chair Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma’s opening plea for the discussions to focus on the practical ways in which effective industrial policies could be implemented, much of the debate was relatively technocratic – a shopping list of good policies for industrialisation. Perhaps it’s too much to hope for in a large set-piece international forum, but I was disappointed there wasn’t a deeper exploration of the politics and compromises that drive these decisions.

If you’d like to receive an occasional email keeping you up to date with the latest IRIBA news and research, you can now sign up here (or at the bottom of the page).

The first edition was sent out earlier this week featuring, among other things, an exclusive, limited edition photo of Armando Barrientos in full flow at the LSE. Don’t miss out!

Most of the research on Bolsa Família looks at its aggregate impact at a national level, so IRIBA researchers decided to focus instead on what happens to school attendance and the labour supply at the municipal level.

This week, Dario Debowicz talked PhD students at the Brooks World Poverty Institute through the detailed methodology involved:

Methodology: Quantile regression panel data for Bolsa Familia from The International Research Initiative on Brazil and Africa (IRIBA)

The research found significant differences in outcomes across municipalities for certain outcomes. Adult labour force participation rates, for example, rise with programme coverage at the municipal level. Female school attendance also rises much more significantly in poorer municipalities than those that are better off.

These results suggest that Bolsa Família has had positive and stronger effects on the more disadvantaged municipalities.

Read the working paper: ‘Antipoverty transfers and inclusive growth in Brazil’.

IRIBA’s research directors, Armando Barrientos and Ed Amann draw together the conclusions from the first phase of the project. Cross posted from ELDIS.

Brazil’s ascent to prominence on the international economic stage has been a prolonged affair. Perhaps the most curious feature of Brazil’s economic and political development has been an enduring discrepancy between the country’s size and obvious potential on the one hand, and its surprisingly low international profile on the other.

Though lower profile than it should be, Brazil’s image has changed rapidly over the last few years. Initially lauded for its social and economic ‘take off’ and resilience following the financial crisis, popular protests ahead of the World Cup then drew global attention to the problems the country still faces. With the 2016 Rio Olympics and an upcoming election that could see Lula’s protégé Dilma Rousseff replaced by the world’s first Green president, attention on Brazil looks unlikely to fade.

In development circles too, Brazil has forged a distinctive approach, in part through its energetic promotion of South-South cooperation. With Brazil’s experience of implementing innovative social policies often the starting point for discussions, African governments, in particular, are looking towards Brazil for inspiration and practical support.

In response to this interest, a team of researchers from Brazil, the USA, and Europe, coordinated by The University of Manchester, have come together to examine if there is a Brazilian development model and the ways in which this experience could best inform individual African countries. Following the publication of 12 working papers, looking at different aspects of agriculture, macroeconomic policy, social policies and labour market intuitions, we contend that Brazil does indeed possess a distinctive model of development.

Since the mid-1990s, despite occasional short-lived crises, Brazil appears to have embarked on a new developmental trajectory in which reasonable growth performance has been combined with an increasingly effective assault on poverty and inequality. The pro-poor character of economic growth in Brazil during the contemporary era stands in marked contrast to the experience of previous boom periods.

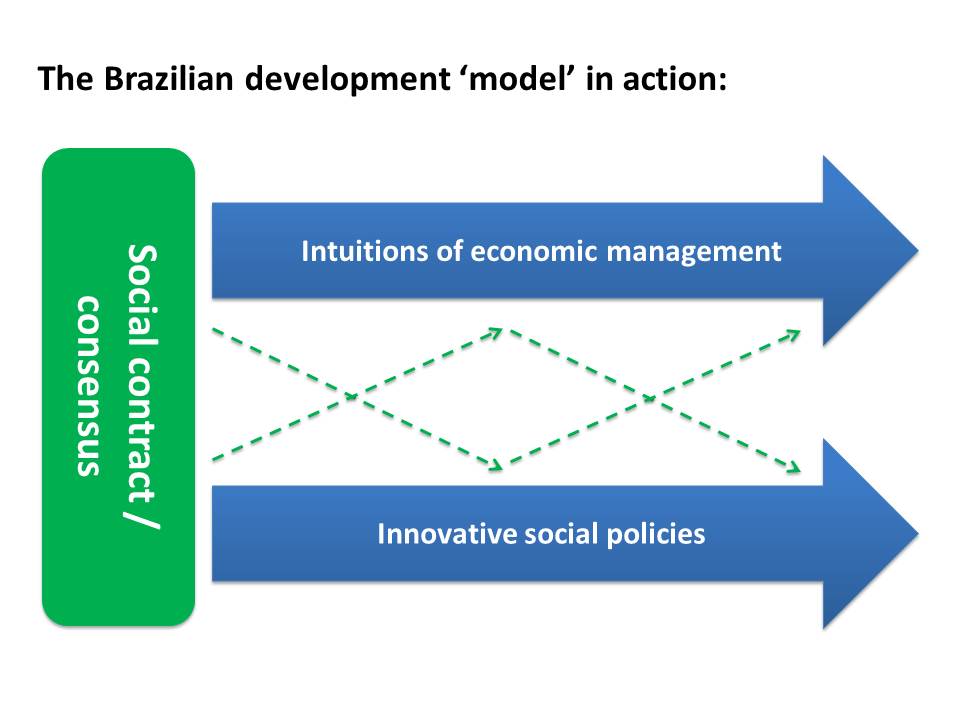

Our assessment is that a unique combination of economic and social policies is primarily responsible for the unexpected success shown by Brazil. Specific features of the institutions of economic management developed after the stabilization plan of 1994 combined with innovative social policies and a favourable social contract, have set a new course for Brazil.

A renewed consensus or ‘social contract’ is fundamental in setting the conditions for a positive evolution of these institutions. It ensures economic and social policies work together and reinforce each other. The 7% rise in Brazil’s tax/GDP ratio from 1995-2010, which funded a significant expansion of social assistance transfers, is emblematic of this effect.

Of course, not all policies fitted together and in the last few years, a variety of signals suggest the Brazilian model could be running against hard constraints. The recent economic slowdown and eruption of popular protests in mid-2013, if nothing else, serve to underline the fact that Brazil’s economic and social reforms are still very much a work in progress.

We believe that the specific combination of economic and social policy at the core of Brazil’s success merits close attention by other developing countries. As the IRIBA project continues to develop, we hope to shed further light on how the Brazilian experience can help inform the development dilemmas facing many African countries.

Is there a Brazilian model of development? from The International Research Initiative on Brazil and Africa (IRIBA)

nbsp;

Read the working paper: Is there a new Brazilian development model?

Read the other IRIBA working papers.

Professor Stephan Klasen is head of the Ibero-America Institute for Economic Research at the University of Göttingen and co-author of the IRIBA working paper on the impact of SENAI vocational training in Brazil and its implications for African countries.

Professor Stephan Klasen is head of the Ibero-America Institute for Economic Research at the University of Göttingen and co-author of the IRIBA working paper on the impact of SENAI vocational training in Brazil and its implications for African countries.

This year’s meeting of the Poverty Reduction, Equity and Growth Network, a network of researchers and policymakers focussing predominantly on poverty and inequality issues in Africa, focussed on employment strategies and industrial policy as key elements for promoting sustainable inclusive growth in Africa.

The meeting took place in Lusaka and was co-organised by the Zambia Institute for Policy Analysis and Research (ZIPAR) and the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. Despite substantial economic growth, the challenge of job creation remains as serious as ever, and will actually grow in coming decades as the number of young people entering the labour market keeps growing. At the workshop there was therefore much discussion about what kind of growth models, and policy frameworks, were suitable to generate employment-intensive growth.

Here a big point of discussion (and disagreement) was on the opportunities and limits for Africa to integrate more fully into global value chains in manufacturing – supported by appropriate industrial and trade policies – or whether it should focus more on primary-product linked value chains and more local manufacturing and services.

What lessons can Brazil's vocational training offer to Africa? from The International Research Initiative on Brazil and Africa (IRIBA)

Aside from looking to East Asia for guidance on these questions, the Brazilian development model was also discussed in some detail. Brazil also has a large primary product export sector, it has high inequality, and it has used active trade and industrial policy to promote diversification of its economic structure. But the limits of the Brazilian model also became apparent.

As a large economy with a history of import-substituting industrialisation, its industrial sector had a much better base from which to develop (and still struggles to expand); Africa’s challenges (outside South Africa, and maybe Nigeria or Kenya) are much more substantial here. Also, the Brazilian agricultural development model, based on high-tech capital-intensive export agriculture, are only partly relevant to smallholders in Africa who predominate among the poor.

The question of vocational training also received a lot of attention and Brazil’s SENAI system of vocational training was seen as rather promising as it has succeeded in improving the school-to-work transition and reducing the skills gap. To further assess the scope of this training model in Africa, it will be critical to rigorously evaluate the SENAI transplants in Africa that have emerged with Brazilian support as well as the South African vocational training system which has included many of the Brazilian elements.

In short, Brazil’s experience provides many interesting insights and lessons. Their suitability to Africa’s context needs to be investigated in much greater detail.

© IRIBA 2014 | All rights reserved I Google+

Hosted by The Brooks World Poverty Institute