This overview is based on the journal article ‘The role of fiscal and monetary policies in the Brazilian economy: Understanding recent institutional reforms and economic changes’, by José Roberto Afonso, Eliane Cristina Araújo and Bernardo Guelber Fajardo.

Hardwiring inflation into the economy

In the 1960s, military governments promoted far-reaching structural economic reforms in Brazil, creating innovative and stable institutions based on standard international theories and best practice at the time.

In this context, the 1960s saw the launch of the Government Economic Action Plan (PAEG), which was intended to promote stabilisation and a return to growth. The fight against inflation became a priority because it was impossible for the country to progress while suffering from hyperinflation.

With an initial focus on monetary institutions, financial reform focussed on driving growth by creating long-term financing mechanisms, avoiding inflationary public-sector financing and re-attracting private-sector investment to Brazilian industry.

With these goals in mind, important measures were adopted—such as the creation of index linking, under which public debt was issued in Re-adjustable National Treasury Obligations (ORTN) and private securities came under the capital market law. This guaranteed a positive rate of return, protecting savers against inflation and encouraging saving. Compulsory saving mechanisms were also implemented, while investment and financial institutions, the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) and the National Monetary Board (CMN) were all created.

These measures restructured the financial system and led to a resurgence of the market for public bonds. However, they also introduced problems that later led to a great impasse in controlling the country’s inflation.

Index-linking had the effect of adapting the economic system to high inflation and led to past inflation being projected into the future.

Brazil increasingly became recognised as an inflationary economy, allowing further inflation-linking regulations to be introduced, which enabled Brazilians to peacefully coexist with inflation. Index-linking permeated all reforms, with rules for exchange rate and salary corrections, financial asset protection and tax system adjustment, which resulted in conditions that allowed inflation to embark on an apparently automatic trajectory.

The return of hyperinflation

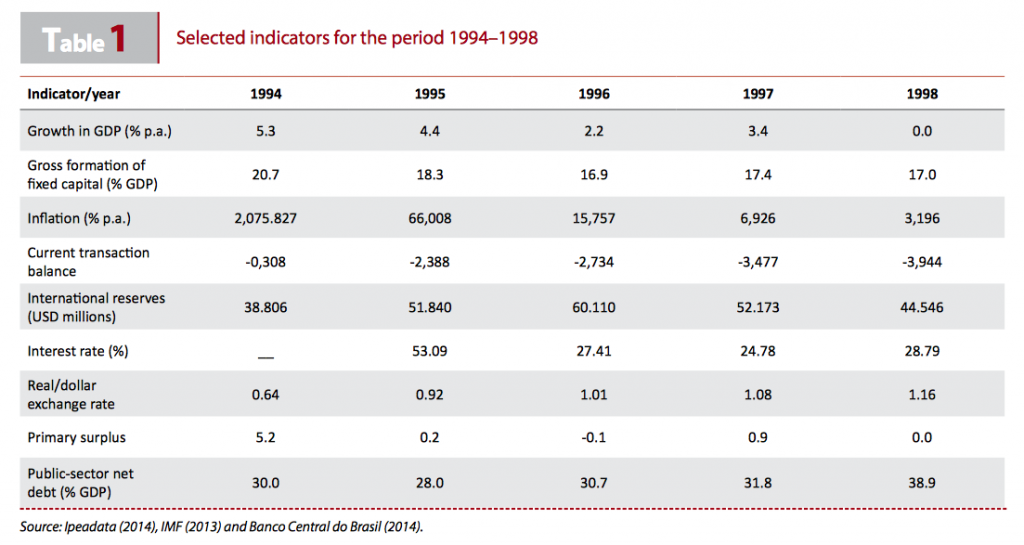

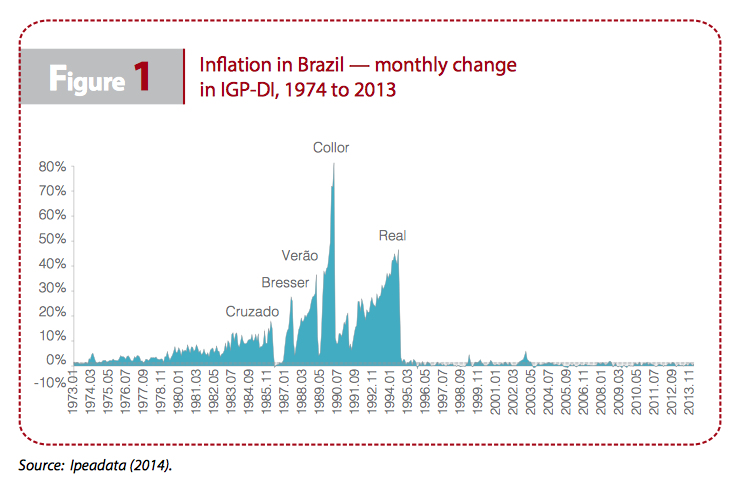

The 1973 and 1979 oil shocks marked the resurgence of inflation in Brazil (see Figure 1), with indexation mechanisms initially allowing the Brazilian population to live with increasingly high rates of inflation.

However, as inflation accelerated, the rest of the economy stagnated. The 1980s are now viewed as a lost decade due to the deep crisis the country suffered. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth practically stagnated, with years of major recession (1981: – 4.3 per cent; 1982: 0.8 per cent; and 1983: – 2.9 per cent). Inflation accelerated significantly even in years of low growth, reaching 100 per cent per year in 1980, accelerating again after the major devaluation of 1983 and reaching 224 per cent a year (on the General Price Index—IGP) in 1984.

The 1980s represented a crisis for the Brazilian development model, which had been in place for almost 50 years—sometimes called the import replacement model. This model had targetted ‘final-stage’ industrialisation, implemented in all sectors of industry, but most companies were unable to withstand international competition.

The second half of the 1980s and first half of the 1990s saw weak attempts to fight inflation in the form of economic plans: the Cruzado Plan in 1986, the Bresser Plan in 1987, the Verao Plan in 1989 and the Collor Plan in 1990, and were characterised by divergent views and theories about controlling inflation. These plans, along with their flaws, eventually helped to formulate the Real Plan—a landmark that ended a cycle of nearly 10 years of ineffectual attempts to combat inflation.

The Real Plan

The formulation of the Real Plan was a watershed moment. In an economy previously marked by hyperinflation, which had already tried a foreign debt moratorium, confiscation of domestic savings and accentuated fiscal indiscipline, the introduction of the Real led to controlled inflation and rebalanced external and public accounts.

The Real Plan was effectively a price stabilisation policy implemented in three distinct phases between May 1993 and January 1999, which can be summarised as: i) short-term fiscal adjustment; ii) de-indexing of the economy; and iii) use of a semi-fixed exchange rate.

Inflation fell significantly and remained at a low level. However, price stability was achieved by using extremely high interest rates and an overvalued exchange rate. It is notable that the period’s macroeconomic system was efficient in controlling prices, despite its adverse consequences in terms of reduced growth, balance of payments deficits and expansion in public debt.

The revalued exchange rate policy altered the previous framework of relationships between the exchange rate, fiscal and monetary policies, and reduced uncertainty about the behaviour of basic prices in the economy, as agents could base their expectations on a predictable exchange rate.

It can be said that the exchange rate target system was highly successful in reversing the process of chronic inflation that affected the Brazilian economy. However, after the financial turbulence caused by the Mexican crisis in 1995, the Asian crisis in 1997 and the Russian crisis in 1998, the country abandoned its fixed exchange rate system due to speculative attacks that reduced foreign reserves.

The exchange rate crisis in January 1999 resulted in a major devaluation of the Real against the US dollar, seeing it fall from a rate of 1.20 in December 1998 to 1.98 in January 1999. This period saw a three-fold change in the macroeconomic regime: the monetary system of exchange rate targets was replaced by an inflation target system; the system of semi-fixed exchange rates gave way to a managed floating exchange rate; and the fiscal system began to pursue targets to create a primary surplus and reduce net borrowing. These three items came to be called the Brazilian macroeconomic tripod.

It is notable that, by adopting the floating exchange rate, the BCB regained control of monetary policy, and the exchange rate became responsible for absorbing external shocks.

In regard to fiscal policy, after agreements with the International Monetary Fund were signed at the end of the 1990s, Brazil put in place a fiscal system with targets for the primary surplus, with the aim of maintaining debt stability and giving the government credibility, thus enabling it to reduce the interest paid on public borrowing at a later date.

In the 2000s, as crises gave way to the longest and most profound economic boom in Latin America since World War II, further reform of fiscal institutions was abandoned.

From the commodities boom to household consumption, increased growth enabled good fiscal outcomes without institutional change.

The 2008 global financial crisis naturally changed this scenario, but Brazil faced it in an idiosyncratic way: with state involvement, as in the rest of the world, but not in the form of higher public investment. Instead, the authorities offered credit to the rest of the economy via state-owned banks at below-market interest rates.

The response to the global financial crisis broke away from the historic Brazilian tradition of addressing crisis with reform, although the government did still use fiscal policy: current expenditure, particularly on social security and benefits, grew faster than the economy and revenue. Fiscal benefits rapidly multiplied, from tax breaks to credit subsidies. In recent years, tax revenue fell and the federal government resorted to stratagems to create a primary surplus artificially1, rather than reducing the fiscal target.

Prospects for the future

Among policymakers there is little impetus to review, much less restructure, monetary, tax and fiscal institutions. Macroeconomic policy remains based on the same tripod as in the late-1990s, with a floating exchange rate, inflation targets and fiscal austerity.

In this context, the outlook is rather confusing and troubling. Public debt and the tax burden have reached higher levels than in other emerging economies. Investment represents an ever-smaller share of the public budget, while the overwhelming volume of spending is committed contractually or politically.

Possibly the greatest contemporary challenge for Brazil is to return to the cycles of institutional reform that were implemented at the end of the 20th century, which could then serve as a reference or example for other emerging economies.

___________________________

References

Afonso, José Roberto, and Eliane Cristina Araújo. 2014. ‘Institutions for macro stability: Inflation targets and fiscal responsibility‘. IRIBA Working Paper, No. 7. Manchester: International Research Initiative on Brazil and Africa. Accessed 6 November 2015.

Almeida. M. 2013. ‘A política fiscal no Brasil e perspectivas para 2015/2018’. In Propostas para o Governo 2015/2018 – Agenda para um País Próspero e Competitivo, edited by F. Giambiagi and C. Porto. Elsevier – Campus.

Barbosa-Filho, Nelson H. 2006. ‘Inflation Targeting in Brazil: Is there an alternative?’ Alternatives to Inflation Targeting, No. 6, September. Amherst, MA: Political Economy Research Institute. <http://bit.ly/1hedu4J>. Accessed 6 November 2015.

Bogdansky, Joel, Alexandre Antonio Tombini, and Sérgio Ribeiro da Costa Werlang. 2000. ‘Implementing Inflation Targeting in Brazil‘. Working Paper, No. 1, July. Brasìlia: Banco Central do Brasil. Accessed 6 November 2015.

Ipea. Ipeadata. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. Accessed 6 November 2015.

IMF. 2013. ‘Brazil. Staff Report for the 2013 Article IV Consultation‘. Country Report, No. 13/312. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Accessed 6 November 2015.

Oreiro, J., L. Punzzo, and E. de Araujo. 2012. ‘Macroeconomic Constraints to Growth of the Brazilian Economy: Diagnosis and some Policy Proposals‘. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 36: 919–939. Accessed 6 November 2015.

Serra, José, and José Roberto R. Afonso. 2007. ‘El Federalismo Fiscal en Brasil: Una Visión Panorámica‘. Revista de la CEPAL, Vol. 91: 29–52. Santiago do Chile: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Accessed 6 November 2015.

Footnotes

1. Such as borrowing from state banks to help finance expenditures.