Leandro Vinicio Carvalho has a major in Economics at University of Sao Paulo, Master’s degree in Applied Economics at Federal University of Sao Carlos (Campus de Sorocaba) and is currently a PhD student in Economics at ESALQ/USP. He has working about Monetary Policies, Agricultural Policies, Agribusiness System and Taxing in Agribusiness.

IRIBA research:

Lindsey Carson, a Visiting Scholar and Professorial Lecturer at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), is completing her doctorate at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Law. She also holds an MSc in Development Studies from the London School of Economics (2006), and JD (Hons.) from the University of Pennsylvania (2009). Her research focuses on laws against foreign bribery, anti-corruption reform, and social and economic policy dysfunctions in developing countries, with a focus on Africa. She has published in the areas of law and development, organisational theory, comparative law and economics, and anti-corruption.

IRIBA research:

- Mapping corruption and its institutional determinants in Brazil

- Brazilian anti-corruption legislation and its enforcement

Last week, we teamed up with Johns Hopkins SAIS to debate the Brazilian development model and its potential implications for African countries. Watch the event:

Mariana Mota Prado, author of the IRIBA research on the Brazilian approach to anti-corruption wrote the following comment on the Brazilian elections for the University of Toronto law blog. It’s re-posted here with permission.

Mariana Mota Prado, author of the IRIBA research on the Brazilian approach to anti-corruption wrote the following comment on the Brazilian elections for the University of Toronto law blog. It’s re-posted here with permission.

Last month, Brazil decided to re-elect its President, keeping Dilma Rousseff for another four years in power. The margin of victory was really small (51.6%). The wealthy regions (south and southeast) have largely favoured Dilma’s opponent, Aecio Neves, while the poorest regions (north and northeast) have strongly supported Dilma.

While the elections clearly show a divided country, those who have followed the debates and scrutinised the policy proposals know that the results reflect more than a division based on income levels. The outcome of this election shows a country divided over two very different development projects.

Before the Worker’s Party (PT) came to power with Lula in 2002, the country was ruled by the Social Democrats for eight years. During this time, the Social Democrats (PSDB) created a much-needed stabilisation plan to fight inflation (which had reached 1,000% annually in the early 1990s). However, they also adopted a plan to reduce the size of the state through privatisation, while at the same time creating strong institutions that could support private investments (such as independent regulatory agencies). According to the social democrats, fiscal responsibility, a small state and strong institutions would create the conditions for the private sector to act as engine of growth. In sum, from 1998 to 2002 Brazil has followed an economic agenda very much in tune with the Washington Consensus.

In 2002, the Worker’s Party came to power with the intention to keep the strong pillars that secured macroeconomic stability. However, the Party also came with a plan to increase redistribution and reduce poverty. The results achieved were so impressive that the ambitious anti-poverty programme implemented in Brazil was touted by the World Bank as a model to be followed by other countries. Alongside its redistributive programmes, the Worker’s Party has also strengthened and increased the state’s presence in the economy. This has been accompanied by an increased role for the Brazilian Development Bank, and a number of informal institutional changes that have undermined the institutional make-up of the previous model. The independence of the Central Bank is a topic that gained a surprising and unexpected prominence during the campaign. Along the same lines, the independence of regulatory agencies for infrastructure sectors has also been a concern, but one been confined to a more specialised audience.

The candidates also had opposing views on foreign policy, which were also in line with their views of domestic policies. As one blogger described: “Rousseff’s vision is clearly represented by the BRICS model, which constitutes a multipolar challenge by the some of the world’s biggest economies to the hegemony of the United States.” In contrast, according to The Economist: “Mr Neves would seek closer ties with developed countries (a main source of technology and markets for Brazil’s manufactures) without abandoning Asia or Africa. In South America, he’d “de-ideologise” policy, rather than team up with Venezuela, Argentina and Cuba.” In sum, not only were the candidates not seeing eye-to-eye on economic policy, but their differences in the domestic sphere echoed into their thoughts about how Brazil was supposed to relate to the rest of the world.

Brazilian citizens were utterly divided between these two options and for a good reason. The proposals presented to Brazilians during this electoral process are not only very different but represent models of development grounded in irreconcilable premises. On the one hand, liberal (and neoliberal) economists have developed strong arguments on the importance of institutions and the private sector to promote development (combined with free trade and foreign direct investment). This is the model supported by the Social Democrats. On the other hand, there are those who support greater state intervention and a higher degree of protectionism. Such policies have strong roots in Latin America, dating back to the creation of the ECLAC, which was based on structuralist thinking. Today, such views are articulated and strongly supported by prominent scholars, such as Ha-Joon Chang. The influence of this school of thought over the Worker’s Party agenda is undeniable.

So, the decision forced upon Brazilians was a choice between two radically different development models. Considering that this topic has generated fierce debates among development experts for decades, it does not come as a surprise that Brazilians were also divided over the choices. There is no conclusive empirical evidence supporting one model or another. As Brazilian voters had very little information to determine where each of these models would take them, they decided to turn to the past in search of guidance. By and large, the poor have chosen the development model that has mostly favoured them in the last 12 years. The wealthy, in turn, have favoured the model that promised higher rates of growth, which is what has benefitted them most in the past. While the results may be a victory for lower classes and for those concerned with poverty and inequality, they have not reduced the country’s anxieties about its future. The redistributive and interventionist model won in the ballots, but only time will shows if this was indeed the right path for the country in the long term.

Photo credit: Adrien Sifre (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For the Brazilian minister for Social Development, Tereza Campello, ‘teaching a man to fish’ is only part of the story. You also need to show him the way to the river and if he’s too hungry to fish in the first place – just give him some of your fish!

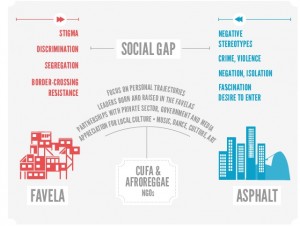

Campello’s impassioned take on the responsibility of the state to play an active role in the fight against poverty and inequality came at the end of a fascinating conference organised by Favelas@LSE. The findings of its Underground Sociabilities project knitted the day together, to give a unique insight into the experience of Brazil at both a national and street level – through the eyes of Minister Campello and some of Rio’s favela dwellers.

Professor Sandra Jovchelovich set the tone for the day, with an outline of the Underground Sociabilities findings. The project looked at the lives of people living is Rio’s favelas and their use of cultural organisations to challenge negative stereotypes and influences. The (free) e-book is well worth a read.

Campello, followed by IRIBA’s Armando Barrientos outlined the nature of progress at the national level in Brazil. Campello was one of the original architects of Bolsa Família and is clearly proud of the impact it has made, particularly on levels of extreme poverty experienced by children. In 10 years, the number of children living in extreme poverty has fallen by 89% and now stands at under 1% of the population.

Despite the progress, Campello is clear that the job is not yet finished. Millions may have escaped from extreme poverty, but they’re still very poor. A key aspect of the government’s drive to make further progress is the creation of a full-blown welfare state. This has been the intention from the start, but often gets missed in the focus on individual programmes (like Bolsa Família).

Corroborating the IRIBA findings on the importance of the social contract to addressing poverty in Brazil, Campello repeatedly stressed the responsibility of the state to root out poverty. This is encapsulated by recent efforts to actively seek out the few hundred thousand hard to reach Brazilians still living in extreme poverty.

Arguing that inclusive growth was the distinctive feature in Brazil’s development performance, Professor Barrientos outlined the main IRIBA findings and his own research on the impact of Brazilian antipoverty transfers:

Reflecting on the implications for the UK (and potentially other countries), he highlighted:

- That the contribution of effective social policies is essential to secure inclusive growth

- That social investment is complementary to growth and human development

- The importance of sustaining social contracts based on a concern for the least advantaged

In contrast to the dreaded post-lunch slump featured in many day-long conferences, the infectious energy, enthusiasm and ideas of favela activists like CUFA’s Nega Gizza and citizen journalist Rene Silva dos Santos was startling. Their very real struggles with poverty, violence and a lack of opportunity in Rio’s favelas was set against their incredible sense of dynamism and agency.

While the minister discussed the social contact in more overt terms, I realised that the attitude and contribution of people like Nega and Rene is a vital aspect of Brazil’s much larger project. Although they’d both experienced difficult times and setbacks, both had an inspiringly positive outlook for themselves and their communities.

The sense of both a bottom-up and top-down vision and action towards improving life for all Brazilians was palpable – and certainly helped me to see the IRIBA findings in a much more vivid context.

We recently published a briefing giving a 10-point summary of our main findings from the first phase of the IRIBA project. This has been well-received, particularly by some of our academic colleagues. However, we wondered if the list could be boiled down further, especially for the busy policymakers out there.

Tomorrow, Armando Barrientos is presenting a summary of the IRIBA findings at the UK-Brazil social development dialogue, alongside the Brazilian minister for social development, Tereza Campello.

We’ve used this opportunity to get the 10 points down to 5 – see what you think:

1. Brazil’s impressive development progress is grounded on a strong social and political consensus on the need to tackle poverty and inequality, through a stable economy and inclusive growth.

2. Brazil developed a comprehensive and effective set of institutions to manage the economy providing both stability and the fiscal space to support innovative social policies.

3. More effective institutions helped raise the productivity of agriculture, enabling Brazil to become a major exporter. Long-term government investment in agricultural research provided a crucial boost.

4. Inclusive growth has been achieved through a combination of labour market (minimum wage) and social policies (social pensions and human development income guarantees) ensuring the benefits of economic growth reach the poorest Brazilians.

5. Despite significant progress, Brazil still faces big challenges. Investment in infrastructure has proved insufficient and the effects from the global economic slowdown is resulting in considerable stress on the social contract.

Does this ring true to you? Are there any major elements that we haven’t mentioned? Could it be even snappier? Please let us know in the comments below.

Photo credit: Escadaria Selaron Rio de Janeiro Brazil” by Boris G (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The next edition of the African Economic Outlook will investigate how to bridge the urban-rural divide in African countries. With many African states struggling to translate impressive headline rates of economic growth into tangible improvements for the poorest people living in rural areas, this is a crucial issue.

Reducing the gaps between urban and rural areas has been a real feature of Brazil’s development progress over the last 20 years. Greater connectivity and less labour market segmentation between cities and the countryside have helped to catalyse inclusive growth in Brazil, lifting 40 million people out of poverty in the process.

To help prepare the 2015 African Economic Outlook, we recently presented at an experts meeting hosted by the OECD. Here are the slides:

Spatial inclusion in Africa: Learning from Brazil from The International Research Initiative on Brazil and Africa (IRIBA)

More detailed information on urban-rural issues is also available in this policy briefing.

We’re teaming up with the Johns Hopkins School of Advance International Studies (SAIS) in Washington to hold a debate on the Brazilian model of development and its implications for African countries.

Brazil has emerged as a globally significant economic power in the last decade, achieving inclusive growth that has reduced poverty and inequality.

Does this constitute a distinct new ‘model’ of development? And with many African countries currently failing to translate growth into concerted poverty reduction, could Brazil’s experience offer a way forward?

Riordan Roett, Director of the SAIS Latin American Studies Programme and author of The New Brazil will moderate the debate, which will also feature:

- Ed Amann, IRIBA research director, University of Manchester

- Ernani Torres, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro

- Mariana Mota Prado, University of Toronto

- Lindsey Carson, SAIS

Tickets and live stream

The event will be held on Thursday November 20 at 12.30-2.00 EST (5.30-7.00 GMT) and you can apply for tickets here. There will also be a live stream, which will be available via this link.

With Dilma Rousseff narrowly winning a second term as president of Brazil, IRIBA research director Ed Amann looks at the four big issues her administration must grapple with over the next four years:

-

Consensus for reform

The achievement of consensus inside and outside Congress to push through difficult reforms was a hallmark of the successful real stabilisation plan in the 1990s. Yet, it is proving harder to build such a consensus today, certainly among the political elite. The case of long-delayed (and much-needed) fiscal reform is a telling example. During the 1990s, a sense of crisis proved sufficient to galvanise politicians and society at large behind economic stabilisation. The current absence of crisis makes such a trick harder, but not impossible, to pull off today.

-

Effective macroeconomic management

The counter-inflationary framework developed during the 1990s and early 2000s remains in place and is unlikely to be seriously amended. Although effective at restraining prices to single digits (inflation is forecast to end the year at 6.3%), the high interest rates check economic growth. This has consequences for the speed at which poverty can be tackled and represents a real challenge in the short to medium term.

-

Targetted social policies

The most high-profile aspect of Brazil’s successful attempt to drive down poverty has been targetted social policies, among them the Bolsa Família. Many on the left and centre grounds of Brazilian politics would like to see their scope extended, with more emphasis given to improving access to quality education and public health services. The objective is to endow poorer groups with the skills they need to break intergenerational cycles of deprivation. Whether such ambitions can be soon realised is open to doubt. In the absence of meaningful fiscal reform, and with faltering growth, the financial scope for expansion is very limited.

-

The external environment

Future prospects for inclusive growth partly lie outside Brazil’s control. The state of the global economy will have a critical influence on the speed at which the domestic economy grows. The unwinding of quantitative easing and softening commodity prices will make it harder for Brazil to export and draw in investment. This will dampen growth prospects and further limit the fiscal space for spending on social programmes.

It is clear that the Rousseff administration faces serious challenges if it is to build on the accomplishments of recent years. However, Brazil is assuredly not in crisis. The popular clamour for progressive reform and social justice is also louder than ever. Opportunities for positive change exist, but it will take determination and persistence to seize them.

Read more on the key elements of the Brazilian development model.

At the start of the IRIBA project a year ago, co-research directors Armando Barrientos and Ed Amann presented their initial thinking on the Brazilian model and its implications for African countries to a UNU-Wider conference on inclusive growth.

With the first phase research now concluded, their take on the nature of the Brazilian development model has been published as a UNU-Wider working paper. The paper expands on the IRIBA synthesis report, particularly in highlighting the specific policy implications for African countries.

However, if you’d prefer a summary of the research, we’ve just published our 10 key findings on the Brazilian development model. If you think we’ve missed anything, please let us know below.

© IRIBA 2014 | All rights reserved I Google+

Hosted by The Brooks World Poverty Institute