This overview is based on IRIBA Working Paper 12: ‘A more level playing field? Explaining the decline in earnings inequality in Brazil, 1995-2012’, by Francisco H. G. Ferreira, Sergio P. Firpo and Julian Messina.

Declining inequality levels in Brazil

Long one of the world’s most unequal countries, Brazil has experienced a significant reduction in income inequality since its macroeconomic stabilisation around 1994-1995. The Gini coefficient for the country’s distribution of household per capita income fell by 12 per cent from 0.59 in 1995 to 0.52 in 2012.

The decline was particularly pronounced after 2003, when average incomes grew relatively rapidly—by as much as 40 per cent overall—and poverty fell sharply. Brazil was not alone: similar trajectories were observed in a number of other Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Peru and Ecuador, over the same period1.

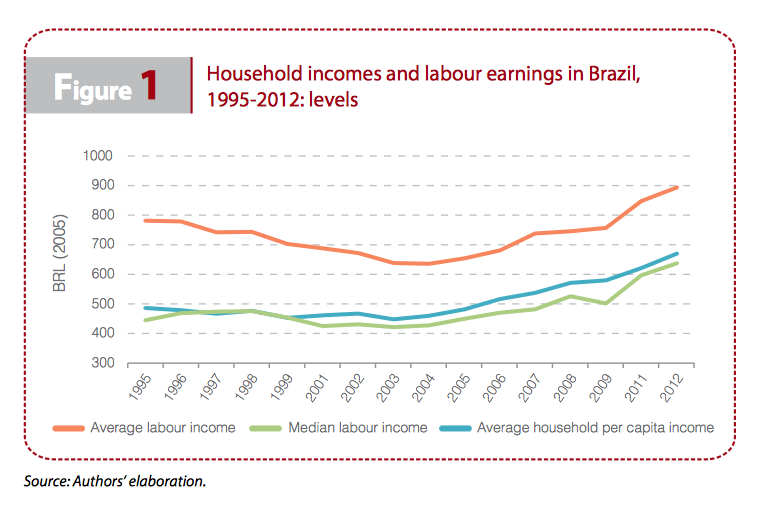

Figure 1 suggests that it may be helpful to distinguish between two sub-periods. From 1995 to 2002, earnings and household incomes were stable or declining. The situation changed around 2002-2003, when all three series began to trend sharply upward. Average earnings in the labour market, for example, experienced an increase of about 40 per cent between 2002 and 2012. Median earnings and household income also grew rapidly in this second sub-period.

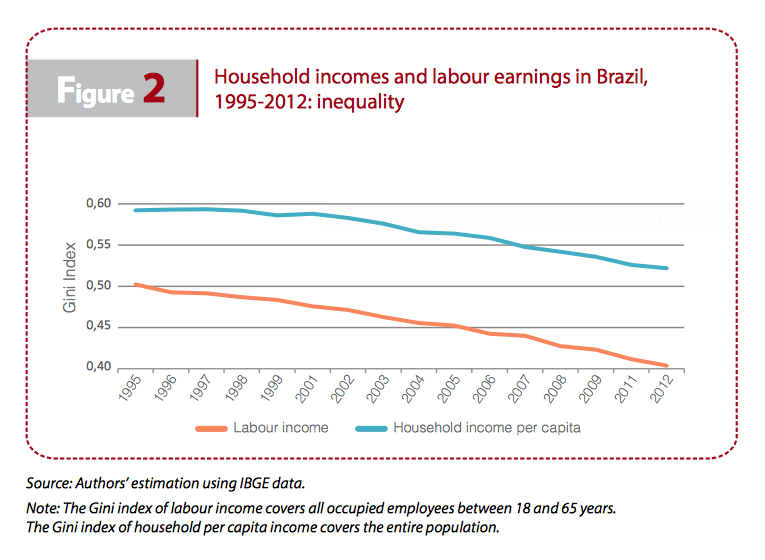

However, there is no correspondingly sharp break when one looks at the trends in inequality, rather than in levels. Figure 2 shows the point estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals for the Gini coefficients of total household income per capita (in purple) and of labour earnings (in red).

Between 1995 and 2002, the decline in income inequality is clearly less rapid than that in labour earnings, for which the Gini coefficient loses three points. But both appear to be falling throughout the period. The second sub-period sees a continuation of the decline in inequality in labour earnings and an acceleration of the decline in household incomes.

Over the full 17-year period, income inequality falls by about 12 per cent, and earnings inequality by as much as 20 per cent, when both are measured by the Gini coefficient.

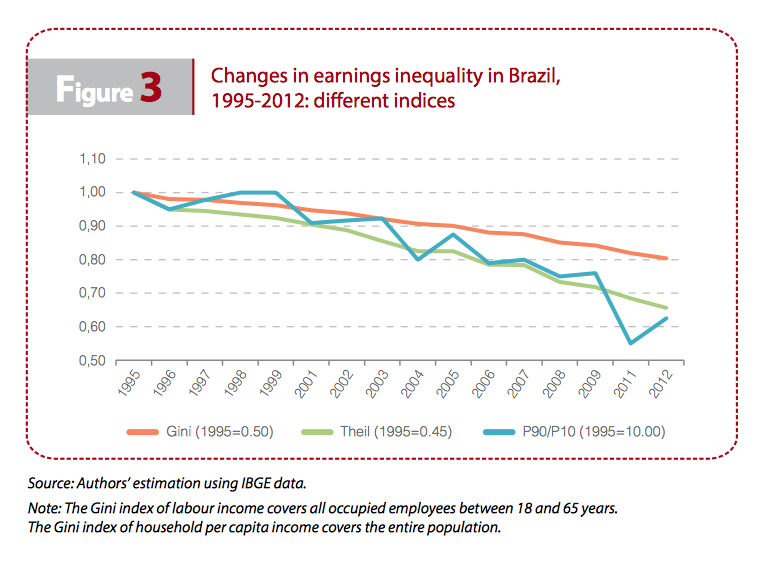

Furthermore, Figure 3 shows that the decline in earnings inequality is robust to the choice of index: the reductions are actually larger when measured by the Theil (T) index, and by the 90–10 percentile ratio, at 34 per cent and 37 per cent, respectively.

Key findings

Unlike most of the previous literature on the subject, our results highlight the importance of demographic, spatial and institutional factors in explaining the decrease in earnings inequality over the period being analysed.

While increases in the stock of human capital in the Brazilian labour force—both in terms of years of education and experience—account for an important share of the increase in levels of pay, human capital is a relatively small contributor to the decline in inequality—and then only because of falling returns to schooling and experience (the endowment component of the human capital effect increased inequality).

Institutional factors play a role—largely through the increase in the share of formal employment. Perhaps most surprisingly, a substantial share of the decline in earnings inequality can be attributed to lower gender and race wage gaps, and to lower urban and regional wage premiums, conditional on educational and institutional factors. Together, these factors account for the reduction of 6.3 of the change of 10 Gini points between 1995 and 2012.

Which factors have helped to reduce inequality?

Much of the popular discourse on this subject has typically stressed the role of fiscal redistribution as a key driver of Brazil’s decline in inequality. In 2003, Brazil’s federal government launched a conditional cash transfer (CCT) programme—Bolsa Família—which has since reached upwards of 50 million people and become one of the world’s largest CCT programmes.

Although Bolsa Família and other fiscal redistribution programmes—such as the Benefício de Prestação Continuada (BPC) and non-contributory rural pensions— have indeed contributed to the reduction in household income inequality, the best available estimates put this contribution at 35–50 per cent of the overall decline (Barros et al. 2010; Azevedo et al. 2013).

Another 10 per cent or so has been attributed to demographic factors—chiefly the rapid decline in family size, which has been most pronounced among poorer households.

The remaining 40–55 per cent of the decline in inequality in household incomes is attributed to changes in the distribution of labour earnings.

The dominant narrative in the literature attributes that decline primarily to human capital dynamics: a substantial increase in years of schooling for working-age adults has translated into a rising supply of skills, followed by a decline in the returns to those skills in the labour market (revealing, presumably, that demand for skills has failed to keep pace with supply).

We find that the decline in earnings inequality between 1995 and 2012 was driven primarily by changes in the structure of remuneration in the Brazilian labour market, rather than directly by changes in the distribution of worker characteristics.

These changes in pay structure can be understood very straightforwardly as declines in various different wage premiums. In addition to falling schooling and experience premiums, the period was also characterised by reductions in the gender wage gap (with women’s earnings rising faster than men’s), the racial wage gaps (with wages for people of colour rising faster than for whites) and the urban–rural wage gap (with wages rising faster in rural areas). Each of these gaps was, of course, estimated conditionally on the full set of observable characteristics.

Another gap whose narrowing contributed to the overall equalisation was that between formal (com carteira) and informal (sem carteira) employees. While these changes in the structure of the labour market are equilibrium phenomena, which reflect market forces such as an increase in the bargaining power of workers vis-à-vis their employers, we argue that they also reflect changes in enforcement patterns by government institutions.

Minimum wages and informality had very different effects during the two examined sub-periods. Starting with the most recent changes, the joint impact of formalisation and minimum wages was very positive for average earnings between 2004 and 2012.

This positive impact was largely driven by the evolution of the returns to formal employment, which contributed to an increase in average earnings of some 4 per cent, and by changes in the composition of workers affected by the minimum wage—which contributed with a 3.5 per cent increase in earnings, while changes in the returns added 1.8 per cent.

In sharp contrast, even if 1995–2003 was a period of relatively slow growth in the minimum wage, an increasing number of Brazilian workers fell below mandated minimum wages.

Compositional changes associated with a rising share of workers below the minimum wage between 1995 and 2003 account for some 2 per cent of the observed reduction in average earnings during this period.

All in all—and in stark contrast to earlier documented periods—the story of these 17 years was a happy one for Brazilian labour markets. Unemployment fell, and earnings rose. Not only did earnings rise on average, but they rose the most for those groups of workers who used to earn the least.

There was indeed a compression in the schooling wage premium, which used to be unusually large in Brazil. But equally impressive were the reductions in wage gaps among workers who are observationally equivalent in terms of their human capital but differ along such dimensions as race, gender, location and type of job.

Is the Brazilian experience relevant to African countries?

Brazil’s performance has naturally attracted widespread attention, among both researchers and policymakers in other countries. Interest has been piqued in Africa, for example, among a handful of countries—including South Africa, Namibia and Botswana—which are also characterised by high levels of inequality.

Brazil is often seen as a more relevant case study for these countries than, say, nations in Europe or North America; given that it is also a developing country, albeit with somewhat higher levels of per capita income. It is also a primary commodity exporter, benefitting, at the time, from the commodity price booms. It is natural, therefore, that there should be interest in whether there might be any lessons from the Brazilian experience with poverty and inequality reduction in a context of rising incomes.

Policy implications

Are there any lessons to be drawn from this analysis for African countries embarking on their own policy struggles for a fairer and less unequal labour market? This is a difficult question, because local context and institutions matter a great deal, and there are non-trivial differences between Brazil’s economy and those of most African countries. Nevertheless, four general implications appear to be broad enough that they must apply, in some locally coherent form, to most other countries:

- An educated labour force is more productive, and, if education is promoted wisely, with a focus on primary and secondary levels, it leads to greater prosperity and greater equity.

- All forms of discrimination—among the sexes, ethnic groups, etc.—tend to be both inefficient and inequitable. Encouraging female education, a reduction in fertility rates and greater labour force participation has contributed to growth in average earnings, and to a less unequal income distribution in Brazil.

- Integrate the rural areas, and the workers who live there: greater connectivity and less labour market segmentation between cities and the countryside are pieces of Brazil’s recently successful strategy in the fight against poverty and inequality.

- And finally, do not fear fiscal redistribution: well-designed transfer programmes are perfectly consistent with vibrant labour markets, with rising average wages and declining dispersion.

___________________________

References

Azevedo, João Pedro, Gabriela Inchauste and Viviane Sanfelice. 2013. ‘Decomposing the Recent Inequality Decline in Latin America’. Policy Research Working Paper, No. 6715. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Barros, Ricardo, Mirela de Carvalho, Samuel Franco and Rosane Mendonça. 2010. ‘Markets, the State, and the Dynamics of Inequality in Brazil’. In Declining Inequality in Latin America: A decade of progress?, edited by Luis Felipe López-Calva and Nora Lustig, chapter 6. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Ferreira, Francisco, Phillippe Leite and Julie Litchfield. 2008. ‘The rise and fall of Brazilian inequality: 1981–2004’. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 12(S2): 199–230.

IBGE. 1995–2012. National Household Sample Survey. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro

de Geografia e Estatística.

López-Calva, Luis Felipe, and Nora Lustig, eds. 2010. Declining Inequality in Latin America: A decade of progress? Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Footnotes

1. See López-Calva and Lustig (2010) for the classic account of this recent decline in Latin American inequality.